A

statistics

professor

used

his

expertise

in

calculating

probabilities

to

come

up

with

a

98

winning

percentage

for

Tim

Hortons

popular

Roll

up

the

Rim

contest.

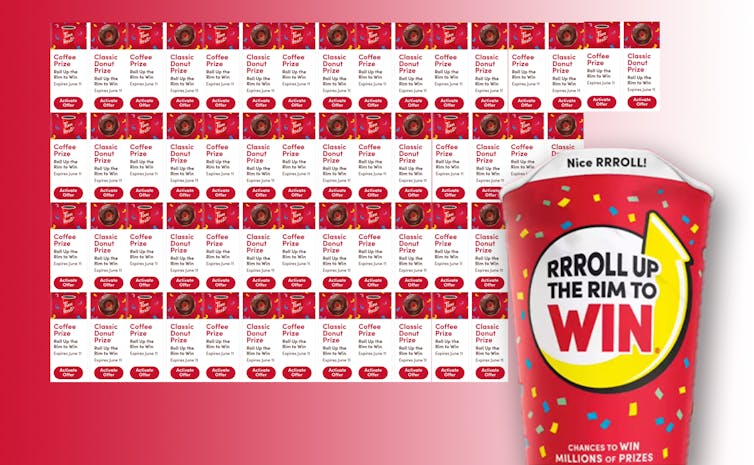

(Photo

Illustration/The

Conversation),

CC

BY-NC

A

statistics

professor

used

his

expertise

in

calculating

probabilities

to

come

up

with

a

98

winning

percentage

for

Tim

Hortons

popular

Roll

up

the

Rim

contest.

(Photo

Illustration/The

Conversation),

CC

BY-NC

,

In 2003, geological statistician Mohan Srivastava cracked a Canadian lottery game. After getting a scratch-off ticket as a gift, he spotted a flaw in the game. Putting his probability skills to work, he figured out how to identify winning tickets prior to purchase. It didnŌĆÖt make him rich ŌĆö ŌĆ£beating the game wasnŌĆÖt worth my time,ŌĆØ he said ŌĆö but SrivastavaŌĆÖs experience showed itŌĆÖs very hard to make a truly random game.

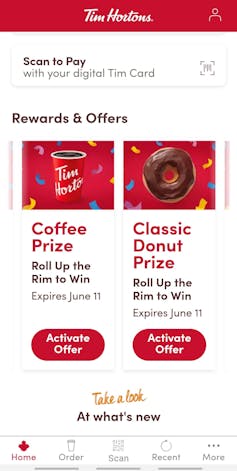

Tim Hortons launched its annual Roll up the Rim promotion in mid-March. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the contestŌĆÖs iconic physical cups were replaced by a digital game on the companyŌĆÖs loyalty app. This change had major implications for how prizes were awarded. It also created an opportunity to shift the odds heavily in your favour.

Under the old format, the mechanics of the game were simple. Tim Hortons would print millions of promotional cups and about one out of every six cups had a prize under its paper rim. If the company expected to sell 180 million coffees during the contest period, then theyŌĆÖd print 180 million promotional cups and make about 30 million of them winners. Stores would then sell the cups until supplies ran out.

This meant that while Tim Hortons couldnŌĆÖt perfectly predict how many coffees theyŌĆÖd sell during the contest period, the odds remained the same. If sales were unexpectedly high, the cups would simply run out sooner. If sales were low, the game would last a little longer. Either way, the number of prizes and the number of cups given out ŌĆö the numerator and denominator of our probability equation ŌĆö were fixed.

ŌĆśDigital rollsŌĆÖ changed the odds

This year, the digital game changed all that. Instead of physical cups, players earned ŌĆ£digital rollsŌĆØ with their purchases. These could be rolled at any time by tapping a virtual coffee cup on the app.

Unlike the physical cups however, Tim Hortons couldnŌĆÖt control how many digital rolls were given out. It depended on their actual sales during the four-week contest period. The number of prizes (the numerator) was still fixed, but the number of entries (the denominator) was out of their hands. They had to find a new way to distribute the prizes.

The

solution,

,

meant

Roll

up

the

Rim

became

a

bit

like

a

slot

machine.

Changes

to

Roll

up

the

Rim

contest

made

the

game

more

like

a

slot

machine.

(Photo

Illustration/The

Conversation),

CC

BY-NC

Changes

to

Roll

up

the

Rim

contest

made

the

game

more

like

a

slot

machine.

(Photo

Illustration/The

Conversation),

CC

BY-NC

Each prize ŌĆö from a coffee to a car ŌĆö was assigned a ŌĆ£winning timeframe,ŌĆØ a short period of time during which it could be won. If you were the first player to tap your app during that timeframe, you won the prize. Tim Hortons could then distribute all the advertised prizes across the contest period and every single one ŌĆö at least in theory ŌĆö could be won.

With some of these winning timeframes as short as 0.1 seconds though, it was certainly possible some would pass with no one playing a roll. Anticipating this, Tim Hortons where any unclaimed prizes were rolled over to another day of the contest, right up until the final day. A prize would only go unclaimed if it wasnŌĆÖt won by the digital roll deadline at midnight on April 21. Although the in-store contest ended April 7, players had an additional two weeks to use their digital rolls.

Prizes rolled over

This

new

game

format

meant

your

odds

of

winning

depended

not

only

on

how

many

digital

rolls

you

earned,

but

also

how

many

others

were

playing.

If

sales

were

low,

then

fewer

people

would

play

ŌĆö

and

more

of

those

winning

timeframes

would

pass

without

the

prize

being

claimed.

Those

unclaimed

prizes

would

roll

over

ŌĆö

and

keep

rolling

over

ŌĆö

until

the

contest

deadline.

ItŌĆÖs

not

known

whether

social

isolation

had

an

impact

on

the

number

of

people

who

played

Roll

up

the

Rim

this

year.

THE

CANADIAN

PRESS/Nathan

Denette

ItŌĆÖs

not

known

whether

social

isolation

had

an

impact

on

the

number

of

people

who

played

Roll

up

the

Rim

this

year.

THE

CANADIAN

PRESS/Nathan

Denette

We donŌĆÖt know for sure because Tim Hortons hasnŌĆÖt announced its sales figures during the contest, but itŌĆÖs reasonable to assume that . Lower sales could theoretically increase the odds of winning a prize through the app, but only if you knew when to play.

As a statistics professor, it seemed appropriate to conduct a small experiment. I knew there was little chance of winning a big prize ŌĆö over 99 per cent of the contestŌĆÖs prizes are coffee or doughnuts ŌĆö but I was statistically curious.

There were other factors to consider. How randomly were the prizes distributed? Were they more likely to be won during the start of the contest? What times of day did people play? Was I more likely to win in the middle of the night? There was no way to know for sure, but I made some guesses and got to work.

An avalanche of unclaimed prizes

Taking advantage of the various ways to earn bonus rolls (such as owning a reusable cup or making a purchase through the app), I racked up 96 entries. I then waited until the very last day of the contest to play them. If my theory was correct, based on statistical models I had calculated before playing, there would be an avalanche of unclaimed prizes waiting to be won.

Waking up at 5 a.m. ŌĆö I wanted to minimize the chance I was playing at the same time as someone else ŌĆö I was finally ready to roll.

On

my

first

play,

I

won

a

free

coffee.

A

good

start,

but

maybe

IŌĆÖd

just

gotten

lucky.

Author

Michael

Wallace

won

67

coffees

and

27

donuts

within

a

few

minutes

by

calculating

the

best

time

to

play

Roll

up

the

Rim.

Author

provided

Author

Michael

Wallace

won

67

coffees

and

27

donuts

within

a

few

minutes

by

calculating

the

best

time

to

play

Roll

up

the

Rim.

Author

provided

I played again. Another coffee. Then a doughnut. Then another coffee. It took nearly 15 minutes to play my 96 rolls.

I lost twice.

I didnŌĆÖt win a car or a TV or even a $25 Tim Hortons gift card, but I didnŌĆÖt expect to. I won 67 coffees and 27 doughnuts ŌĆö my statistical models predicted IŌĆÖd win 66 and 28.

With 94 wins out of 96 entries, I had a 98 per cent success rate. Before the contest, Tim Hortons estimated a playerŌĆÖs chances were just 1-in-9, or about 11 per cent. By finding predictable elements in a seemingly random process, I was able to dramatically shift those odds. IŌĆÖll be telling my probability students about this for years.

Like Mohan Srivastava, I knew this wasnŌĆÖt a get-rich-quick scheme. Your odds of landing a big prize ŌĆö even when almost every roll is a winner ŌĆö are still incredibly small.

The contest rules suggest the value of my prizes if I buy the most expensive coffees and doughnuts possible is about $500. Not a bad return on investment, but IŌĆÖm going to see if Tim Hortons can donate the prizes to my local hospital instead.

, Assistant Professor, Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science,

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .

The story was also picked up by , , and many Metroland Media Group outlets across Ontario. Wallace was also interviewed on the Lynda Steele show on CKNW 980 Vancouver.